|

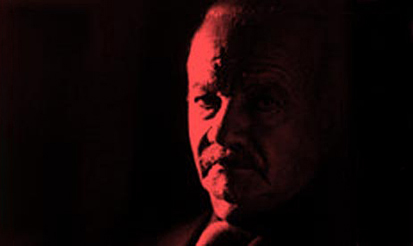

Let's start a little bit off center, with the instrument. The bandoneon is even crueler than diabolical. It basically has four keyboards: one for each hand collapsing and one for each hand expanding. But it's meaner than that, notes line up alongside each other in insistently irrational ways, and the irrationality is different from hand to hand, and the notes shift going in and coming out. The tone is dark, sad and sensuous, yeah, like the Tango and like Astor, himself. Having known Astor, it's impossible to picture him playing any instrument but the bandoneon. And it's hard to listen to the bandoneon played by anyone but Astor. He not only mastered the instrument the way few others ever have, he transformed it: opening up, exploring and using harmonic, rhythmic and percussive options that were only implied in earlier players' works. In fact, the standing bandoneon player was a Piazzolla innovation. "I refuse to look like an old woman knitting," Piazzolla sneered.

Moving closer to the center, and continuing to speak about innovation, we can only talk around Piazzolla and Tango. It's just too big and unwieldy a subject. There are few other cases in modern music of a musician inheriting a musical tradition growing so moribund in its structures and mannerisms, and growing stiff in it's political implications and social function, who so single-handedly transformed it into a breathing, complex, sensual and powerful music. The man introduced outside elements inspired by Jazz and Western European Avant-garde to a stubbornly xenophobic music. He expanded the song structures and added dissonance, counterpoint, complex harmonies, shifted the accents and crossed them. He added a different form of improvisation to his Octet de Buenos Aires in the fifties and changed the melodic role of the instruments for the quintets of the sixties, seventies and eighties. The political and social as well as artistic anger he solicited and the death threats and the years in geographic and artistic exile are famous and crowding legendary.

As is his passion and anger. As is his insistent need to keep changing his music, pushing it farther and farther into more complex, darker and more sensual realms. As is his scowl that made even the most seasoned musicians feel the sharp resonance of their mistakes. As is his humor and his heart (as big as Patagonia.)

Moving to the other side of the center, we have his classic quintet. With only one personnel change, it worked with Piazzolla from 1978 to 1988. Ironically, the one personnel change was Horacio Malvicino, the original guitarist for the Octeto Buenos Aires, rejoining the Maestro. The band, with Fernando Suarez Paz (violin) and Hector Console (bass) coming from classical backgrounds and Pablo Ziegler (piano) and Malvicino (electric guitar) from Jazz and popular musics, developed into one of the tightest ensembles anywhere. Just listen to the form of improvisation they developed with Piazzolla. It's not Jazz nor is it Tango. It's modern, aware of the world, but indigenous Porteno, and their very own. Just listen to their last recording, "La Camorra" suite. It's a brilliant, complex running down of everything you can do with and against Tango form and it's accompanying historical reference. There are knowing, appreciative and critical references not only to four or five of the deepest bandoneon players before Astor, but to the form a Tango band inherits and the way, from the inside out, a form can be restructured to make audible a music that was never there before.

As far as the rest of the above-mentioned center itself is concerned, well you'll be listening to it tonight.

For those more interested in harder edges: "Astor Piazzolla was born in Mar del Plata, Argentina, on March 11, 1921. When he was three years old, his family moved to New York where he learned the Bandoneon, his Lower East Side accent and the National Anthem. He appeared with Carlos Gardel in the motion picture of "El Dia que me Queras" when he was only twelve. Piazzolla returned to Argentina in 1937 and became musical director of Anibal Troilo's Orchestra, one of the main Tango bands of the day. After classical study with Ginastera in Argentina, Piazzolla won a scholarship to study with Nadia Boulanger in Paris in 1954. He returned to Buenos Aires in 1956 to form his Octeto de Buenos Aires and to write for larger orchestras. The Quinteto Nuevo Tango was originally formed in the early sixties, but, as mentioned before, the classic quintet was formed in 1978. Mr. Piazzolla has written numerous film and theater scores and orchestral and chamber pieces. His collaborators have included filmmaker Jeanne Moreau and writer Jorge Luis Borges. Mr. Piazzolla married his beautiful, longtime companion, Laura, on April 11, 1988. Piazzolla disbanded the quintet in July 1988 (La Camorra was it's last recording) and formed a New Tango Sextet in 1989. In August 1990, Astor Piazzolla had a stroke from which he never recovered. He died in Buenos Aires in July 1992."

It feels incomplete for me to end the essay with that. Piazzolla was one of my deepest friends, most demanding artistic collaborators (I did some of the most intense and best work of my life with him), business partners (never forgiving), and my artistic father ("Just don't expect to find yourself in my will," he laughed). To say, "I'll miss him,” sounds silly and thin. It's, of course, more than that. I've missed him for the last two years (his 4 A.M. panic phone calls and all) and will miss him for the rest of my life. The fact that there are a lot of other people who feel the same doesn't make it feel any lighter. But, you know....

Later, Lefty.

—Kip Hanrahan

New York, August 1992

|

|